Donald Trump’s decision to upend decades of Western – and by extension British – foreign policy has caught London badly off-guard. One day, Sir Keir Starmer has had a great day in Washington; the next, a state visit by the President looks like a serious liability.

The sheer scale of the shift in policy required to adapt the UK to a post-American world, and more immediately to meeting the Russian threat, has not really sunk in yet in Westminster. So to aid Kemi Badenoch and the Shadow Cabinet as they formulate the Party’s new policy, we asked our panel of Tory members for their views on some of the big defence questions.

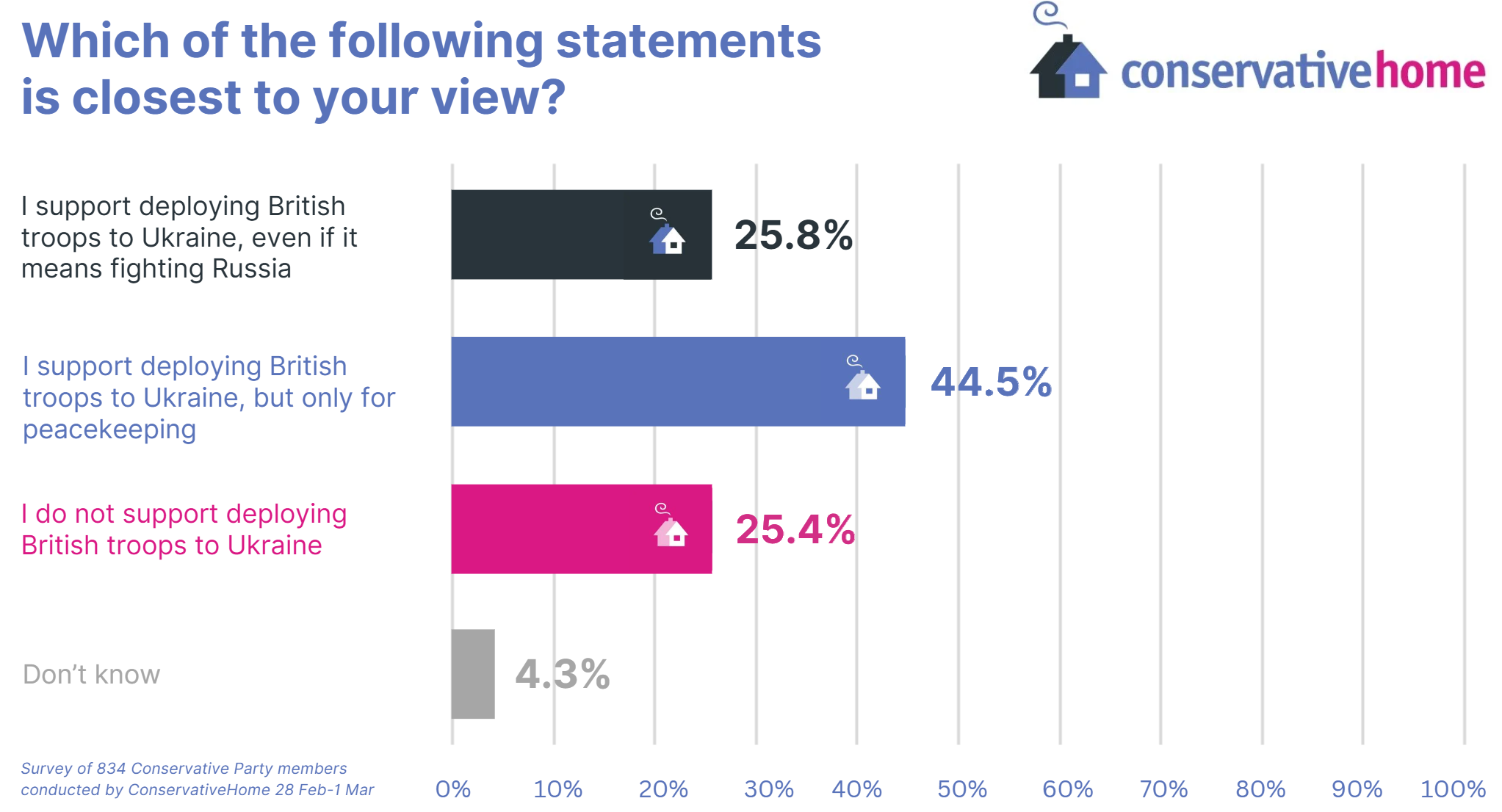

First, we found very strong support for deploying British troops to Ukraine. Just over seven in ten panellists back putting troops on the ground in one form or another, with a quarter saying they would do so even if it meant engaging in combat with the Russian Army. Just a quarter oppose sending troops at all.

The odds of that are remote, of course, with former senior officers warning that the British Army – deployable strength: zero divisions – couldn’t even handle peacekeeping on its own. So it is unsurprising to discover that Conservative members overwhelmingly support a serious uplift in defence spending.

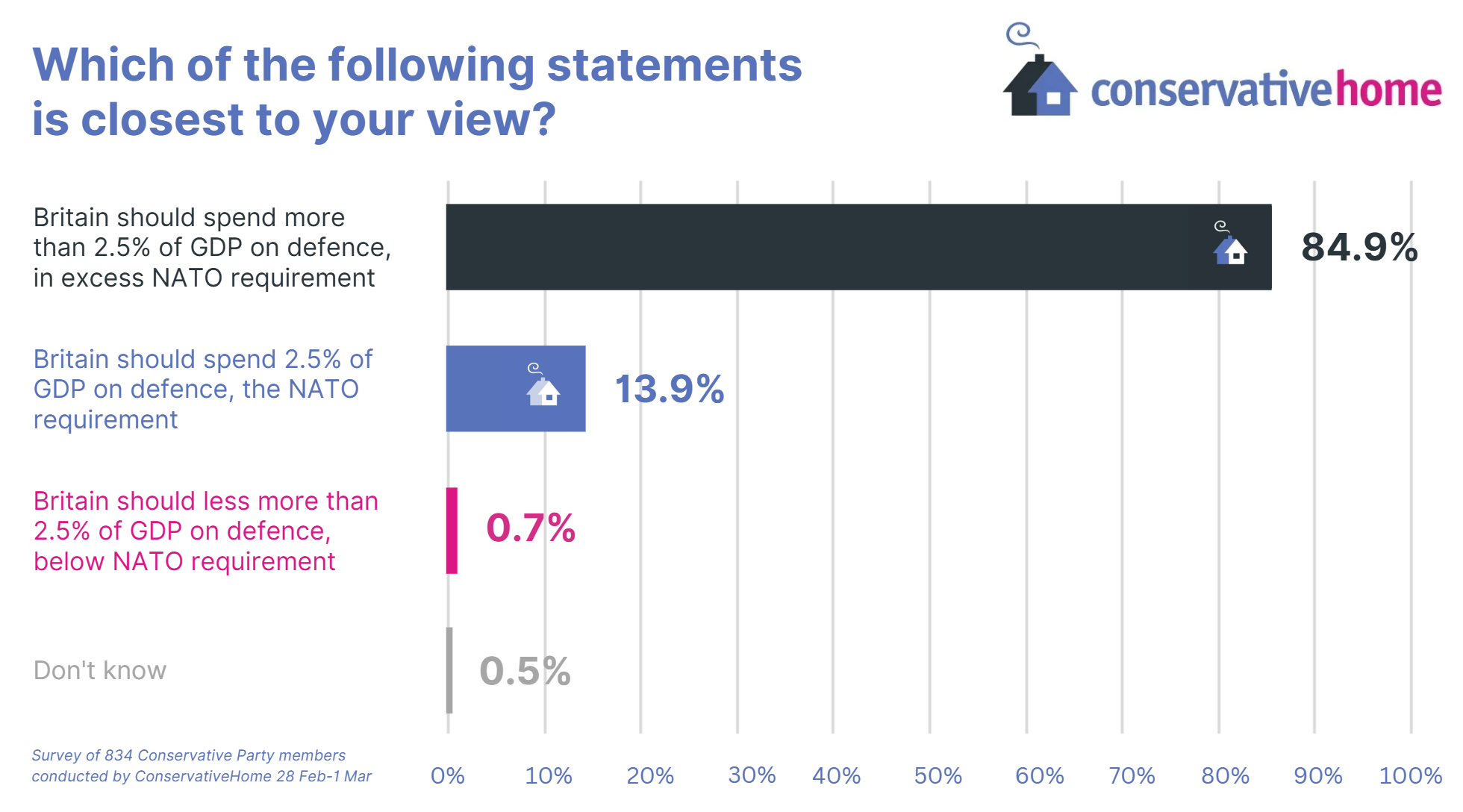

Just shy of 85 per cent of our panel think that it should exceed the NATO commitment of 2.5 per cent of GDP; on this they are in sync with the leadership, which has called for the defence budget to hit three per cent of GDP by the end of this parliament. Nearly all the remainder (14 per cent) support hitting the 2.5 per cent target.

(We did not ask whether this uplift in spending should include moving things into the budget to cook the books, such as the Chagos deal, or moving things out which were previously used to cook the books, as when George Osborne included pensions.)

But it’s easy to support defence spending in the abstract. The meat of the question, given the UK’s fiscal situation, is how to pay for it. As Kemi Badenoch said in her speech to Policy Exchange last month:

“If we approach this challenge of rebuilding as a zero-sum game – as a simple choice between defence spending and public services – we will struggle to persuade the public to back it.”

Yet short of copying Rachel Reeves and waiting for growth to ride across the horizon and spare politicians difficult decisions, it is almost impossible to conceive of the question in other terms; without growing projected tax receipts, public spending is a zero-sum game. Tory members agree: by three to one, our panel took the view that “Britain cannot spend enough on defence without cutting public services or welfare”:

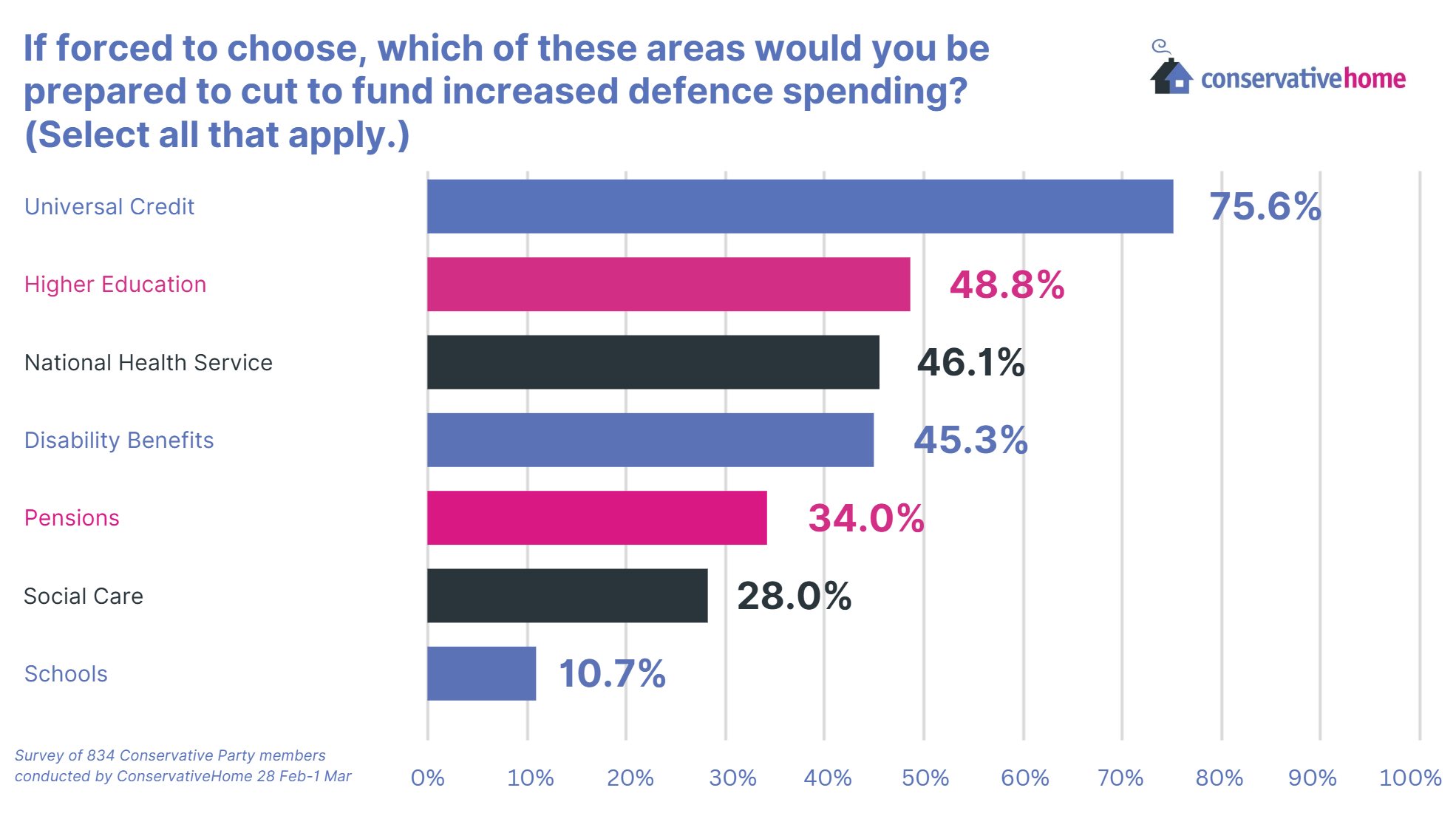

Which leaves the critical question: cut what? For this, we deliberately excluded what we thought the panel might find easy answers, such as overseas aid (where Starmer is in any event cutting away), Net Zero, et al. Instead, we suggested the real big-ticket spending lines, such as health and pensions, plus a couple, such as higher education, which many Tory members might find easier to stomach but would have big domestic political implications.

Top of the list, and way out ahead of the pack, was Universal Credit, which over three quarters of our panel would be prepared to cut to boost defence spending. After that, almost half would choose to make cuts to higher education, the NHS, and disability benefits (such as Personal Independence Payments or Motability).

At the bottom end of the list, only just over a third backed cuts to pensions, and fewer than one in three backed cutting social care. It may in future be worth asking straight up if it is better to cut a means-tested benefit such as UC rather than replace the Triple Lock with something targeted that doesn’t drive up annual payments to already-wealthy pensioners.

However it wasn’t all about the older citizen: only 11 per cent of Conservative members would be prepared to raise defence spending at the expense of schools.