Alexander Bowen is a trainee economist based in Belgium, specialising in public policy assessment, and a policy fellow at a British think tank.

It’s December 1989. A Hungarian and a Belgian walk into a bar. Now this might sound like the start of a peculiarly terrible joke, or even worse one of those oddly big-budget ‘espionage’ films where every non-American character sounds simultaneously German, French & Russia, but it is in fact the start of a 35 year long on-again and very much off-again friendship.

That Belgian is a hardcore right-winger who had, in the five years prior, implemented an austerity program whose fiscal consolidation was worth as a percentage of GDP about twice that of George Osborne’s. Welfare cuts, privatisation, attempting to take on the unions, he had in those five years earned a nickname from the Belgian public – ‘Baby Thatcher’; famous for saying that the job of a finance minister isn’t mathematics it’s to say no.

The Hungarian meanwhile, having returned from working for George Soros in the UK, is a centrist socially liberal student activist who has just jointly won a human rights prize; ideologically far more at home with Blair or Clinton than Thatcher or our Belgian. Nevertheless the two men hit it off, in the next year they meet several times, with the Belgian offering campaign advice as the Hungarian prepares to contest the first real election in 40 years.

Return to today and these two men could not be more different. The Belgian, a one Guy Verhofstadt, the eurofederalising bête noire of Brexit, goes on to become the second longest serving post-war Belgian Prime Minister. In government with the Greens and the Socialists, his views start shifting even if he is still posting budget surpluses for just about the only time in Belgian history. So too does the Hungarian’s views first in his 1998-2002 term and then post 2010 triumph.

I am of course talking about Viktor Orban.

He is a politician who has, at one point or another, espoused every political ideology. When communism was dominant he was a communist, when Solidarity-style trade unionism was the rage he was a trade unionist, when neoliberalism had triumphed he was a neoliberal, when neoconservatism ruled he was a neoconservative, when national-conservatism became the rage he became a national-conservatism.

The only thing that appears to be consistent across this time is his belief in his own self-interest – he is a man who is wedded to ensuring his father can live in a (quite literal) palace not to any particular policy agenda (though I suppose family values does include ensuring your parents live in comfort in their old age). In a certain sense our Hungarian is sort of admirably post ideological.

What I find bizarre then is the recent fetishisation of Orban, and of Hungary, that has developed in conservative circles in recent years not least because it is built on two myths. The first, that of sincerity, that Orban cares about some concept of conservatism, and the second and far more bizarre one – the myth of success. Turn on GB News sometime in the last week and it felt as if much of the programming is praising Hungary’s ‘success’ on fertility, on migration, on the economy, on energy, on family policy. It’s all vaguely reminiscent of Americans in 2016 pointing at Denmark and going “look! socialism” without being able to point to it on a map (a problem Trump is currently helping to resolve).

Former MP Miriam Cates is perhaps the best example of it – out of her 22 most recent posts some 16 are about Orban, or Hungary, or some combination thereof, with two long form articles on the subject. Yet, and without meaning to pick on Miriam specifically here, she was after all working in Hungary at the behest of her employer, to report, but my wider point is there is no evidence base for it.

To start with there’s the mythologisation of Hungary’s fertility policy praising its “intensive programme” and for being the “first Western administration to take seriously the phenomenon of collapsing fertility rates” yet the reality is that the programme hasn’t worked not least because it largely doesn’t exist.

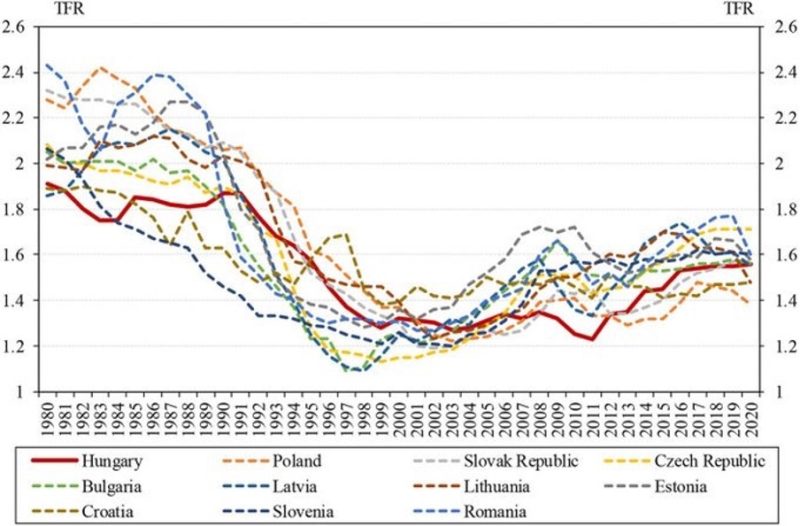

Fertility has risen certainly, but it has risen exactly in line with the region as a whole. In 1990 it had the median fertility of Central & Eastern Europe and today it has… the median fertility of Central & Eastern Europe. National-conservative Hungary has a fertility trend that is functionally interchangeable with that of market-liberal Estonia or social-liberal Slovenia.

As for the fertility policies, what they have been is largely flashy, not functional – far more designed to create headlines than children. ‘Waiving income tax for women giving birth’ is all well and good but anyone who looks at the tax structure can see that it frankly doesn’t matter when someone on an average wage pays just 12.8 per cent in income tax versus 30.3 per cent in social security contributions (not waived) and faces a 27% VAT rate (the world’s highest).

The marginally less flashy policies aren’t any better either. As a percentage of GDP Hungary spends about half of what Germany does on supporting family formation and annualised the fertility increase under Merkel’s 16 years in office is identical to Orban’s post-2010 stretch yet nobody is going to appear on TV championing ‘Merkel style fertility policies’.

As for the ‘family values’ schtick that comes along with it, it has aged like rotten milk now that Orban looks set to lose re-election over a paedophilia scandal which has been bizarrely ignored in every article praising him. Ignoring the scandal in which the Hungarian President, a role approximately equivalent to that of Medvedev’s tenure as Putin’s ‘boss’, pardoned a children’s home director who covered up child sexual abuse, is particularly galling to see from people who, rightly, spend so much time talking about our own grooming gang crisis.

As for Orban’s policies on energy where Miriam points out “On net zero, Hungary has maintained a consistent pragmatic stance, putting energy security above ideology” they have actually been a quiet catastrophe. They, like the fertility policies, are a mirage. On paper Hungary appears to have cheap electricity (though on a PPP basis it’s no different to Sweden’s) but this has been largely achieved through shifting the burden of payment from households to employers. For all we talk about Germany being ‘deindustrialised by net zero’, Hungary today has the EU’s 6th highest industrial electricity price being just as high as Germany’s.

As for the wider economy Orban has managed to make Rachel Reeves look like a bastion of competence. What was once one of Central and Eastern Europe’s richest countries has been turned into the poorest country in the EU with frankly staggering inflation rates in the last few years (running at 17.1 per cent at the same time as the UK recorded 6.8 per cent). Frankly, the economy has been so bad that even the most obvious successes on border control can be partly explained by it – you don’t after all have to deal with illegal migration if nobody wants to illegally migrate to your country in the first place.

At the end of the day, admiration for Hungary’s “success” tells us more about the audiences and commentators than it does about the country itself – it is Budapest as a Barthesian myth. How unfortunate then that the plural of nice (state funded) trips to Hungary is not data.