Jane Green is Professor of Political Science and British Politics at Nuffield College, Oxford. Dr Roosmarijn de Geus is a lecturer in Comparative Politics at the University of Reading.

The Chancellor has announced support to help people with energy bills and the cost of living crisis. Our research shows why this is good politics, as well as essential for the individuals who need it most.

Academics have long explained that left-right politics hasn’t disappeared. Looking at data from 2018 and 2019, we find that economic security was a key driver of people’s voting before the pandemic and the cost of living crisis.

The economic gap between Britain’s younger graduates and non-graduates is growing. Younger non-graduates (women under 50 and men under 40) – who live in all parts of the country – are the least economically secure. They are the most ‘left-behind’ by the economic transformations of globalisation, automation and industrialisation.

Our work shows who was less likely to weather the economic storm that came first with the Covid pandemic and now with rising energy bills and wider inflation. So today’s government support is politically smart as well as necessary. But so is a much stronger focus on economic security into the longer term.

Both major parties – and the Conservatives especially – should keep this front of mind as they prepare for the next election. This isn’t just about household incomes. Having savings, a stable job, a home, the ability to borrow, all help people weather financial storms like the one we are entering now. Not having those buffers is extremely difficult. These people will vote for the party they think can provide them.

Political parties risk misreading these dynamics, partly because of a preoccupation with the “Red Wall”. Whilst the Conservatives made gains in Labour’s heartlands – particularly in 2019 – we show that they have also made gains among older, more economically secure voters in general, including older non-graduate voters who have comparatively high levels of economic security. Ultimately, to win new voters and retain some of those gained in recent elections, the Conservatives have to find new ways to support people who feel economically insecure.

When we think about the electoral consequences of educational attainment and age – the two new big dividing lines in voting behaviour – many people assume a fundamental values divide.

But we show that important economic and values divisions exist both between and within generations. The economic divides between younger non-graduates and graduates aren’t as clearly in evidence among older non-graduates and graduates.

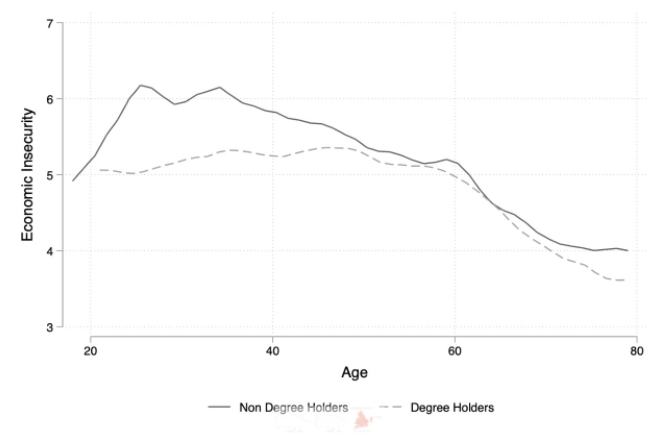

Given that economic security drives voting behaviour, an increase in this gap could have serious implications for the Conservatives. These patterns can be seen here, which shows reported economic insecurity in the British Election Study (BES) internet panel in 2018 across age and educational attainment distribution.

Reported economic insecurity by age and education level (British Election Study internet panel, 2018)

Reported economic insecurity by age and education level (British Election Study internet panel, 2018)

These averages hide differences within these groups, and things are harder for today’s younger graduates than they were. But we emphasise in our report the likely income returns that come from higher education and also the greater family wealth that is correlated with going to university.

That doesn’t make life easy for all graduates by any means, but it is likely to be helping younger graduates at least feel more economically secure on average than younger non-graduates. And the generational differences in wealth that exist – as well as the protections of pensions – have minimised feelings of economic insecurity for older people overall.

The coming economic headwinds are still likely to prove challenging across society. Many pensioners will face extreme difficulties if and when they cannot pay their bills. But young non-graduates felt more economically insecure before these economic shocks began to happen. Many of those people experience extreme circumstances – not being able to afford an emergency expense or having to borrow from friends and family for essentials in the preceding 12 months. As their circumstances change, so could their voting behaviour.

Just as we should not make blanket assumptions about economic security and voting intention, nor should we assume a simple link between economic security and cultural values. Specifically, economic insecurity and support for Brexit (or immigration concerns, or social conservatism) do not necessarily go hand in hand, in the Red Wall or beyond. Examining how these trends diverge by age and education helps us understand the current Conservative electoral base and how it could shift over time, depending on how external factors and its strategies change.

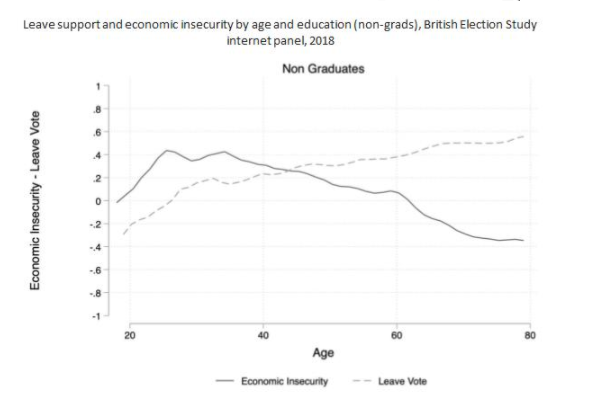

The graph below shows the likelihood of supporting Leave in the EU referendum by age (the dotted line), again using the BES internet panel in 2018, and the average level of feelings of economic insecurity (bold line) by age and education, focusing on non-graduates (and standardised scales to make a comparison). When reading this graph, remember that there are more older non-graduates in the electorate compared to older graduates, and more younger graduates than younger non-graduates (due to the expansion of higher education that has taken place over time).

Leave support and economic insecurity by age and education (non-grads), British Election Study internet panel, 2018

Leave support and economic insecurity by age and education (non-grads), British Election Study internet panel, 2018

Note: graph shows averages across the age distribution. Lines are smoothed local regression lines.

It suggests two clear reasons to support the Conservatives among older non-graduates; their position on Brexit and their sense of economic security. It follows that the Conservative Party should be concerned if these older individuals lose their economic security now, essentially removing one of two key drivers of support. There is no guarantee of holding onto Britain’s most economically secure voters through a culture wars frame, especially with the declining political relevance of Brexit.

Equally, the Conservative Party cannot ignore younger non-graduates. These more socially conservative voters (and some non-voters) are – at least given current Conservative policy directions – the likeliest future potential voters of the party. But there is also no guarantee of winning over Britain’s most economically insecure voters solely through a ‘culture wars’ frame. More economically insecure voters lean towards Labour and they are also more likely to be non-voters than other electoral groups.

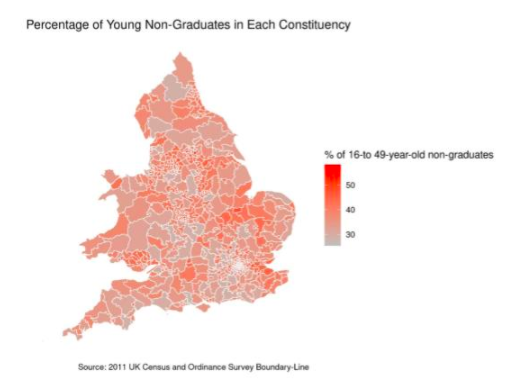

Our research suggests this group could be a key electoral battleground in a number of key marginal constituencies. Using 2011 Census data, the following map shows a high distribution of younger non-graduates in hotly contested seats in England and Wales. People who tend to feel the greatest economic insecurity (younger non-graduates) live in constituencies that Labour has held onto (some seats in the Red Wall but also in many cities, and in south Wales), in seats that the Conservatives won in recent elections, and in key Conservative-Labour marginal seats that have flipped between the two largest parties. Ignoring these distributions could be electorally perilous. So would substantial losses of economic security among older Conservative voters.

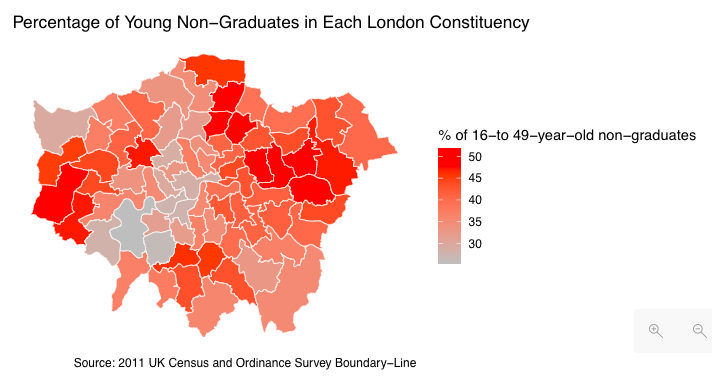

And parts of London (when we zoom in to see these constituencies) are home to higher than average proportions of younger non-graduates, as well as high proportions of younger graduates in others.

And parts of London (when we zoom in to see these constituencies) are home to higher than average proportions of younger non-graduates, as well as high proportions of younger graduates in others.

Parties’ ability to connect with these groups could be pivotal to the outcome of the next election – and they are likely to vote for the party they feel will bring them economic security.

Parties’ ability to connect with these groups could be pivotal to the outcome of the next election – and they are likely to vote for the party they feel will bring them economic security.

Like everybody else, we do not know how the next election will pan out, and our study remains live. We will be adding new data and updating our findings as needed. But our findings so far suggest that each party’s ability to cater to the more economically insecure could be a key factor in their performance at the next general election. If the Tories want to win a record fifth term, they need to understand this.

Jane Green is Professor of Political Science and British Politics at Nuffield College, Oxford. Dr Roosmarijn de Geus is a lecturer in Comparative Politics at the University of Reading.

The Chancellor has announced support to help people with energy bills and the cost of living crisis. Our research shows why this is good politics, as well as essential for the individuals who need it most.

Academics have long explained that left-right politics hasn’t disappeared. Looking at data from 2018 and 2019, we find that economic security was a key driver of people’s voting before the pandemic and the cost of living crisis.

The economic gap between Britain’s younger graduates and non-graduates is growing. Younger non-graduates (women under 50 and men under 40) – who live in all parts of the country – are the least economically secure. They are the most ‘left-behind’ by the economic transformations of globalisation, automation and industrialisation.

Our work shows who was less likely to weather the economic storm that came first with the Covid pandemic and now with rising energy bills and wider inflation. So today’s government support is politically smart as well as necessary. But so is a much stronger focus on economic security into the longer term.

Both major parties – and the Conservatives especially – should keep this front of mind as they prepare for the next election. This isn’t just about household incomes. Having savings, a stable job, a home, the ability to borrow, all help people weather financial storms like the one we are entering now. Not having those buffers is extremely difficult. These people will vote for the party they think can provide them.

Political parties risk misreading these dynamics, partly because of a preoccupation with the “Red Wall”. Whilst the Conservatives made gains in Labour’s heartlands – particularly in 2019 – we show that they have also made gains among older, more economically secure voters in general, including older non-graduate voters who have comparatively high levels of economic security. Ultimately, to win new voters and retain some of those gained in recent elections, the Conservatives have to find new ways to support people who feel economically insecure.

When we think about the electoral consequences of educational attainment and age – the two new big dividing lines in voting behaviour – many people assume a fundamental values divide.

But we show that important economic and values divisions exist both between and within generations. The economic divides between younger non-graduates and graduates aren’t as clearly in evidence among older non-graduates and graduates.

Given that economic security drives voting behaviour, an increase in this gap could have serious implications for the Conservatives. These patterns can be seen here, which shows reported economic insecurity in the British Election Study (BES) internet panel in 2018 across age and educational attainment distribution.

These averages hide differences within these groups, and things are harder for today’s younger graduates than they were. But we emphasise in our report the likely income returns that come from higher education and also the greater family wealth that is correlated with going to university.

That doesn’t make life easy for all graduates by any means, but it is likely to be helping younger graduates at least feel more economically secure on average than younger non-graduates. And the generational differences in wealth that exist – as well as the protections of pensions – have minimised feelings of economic insecurity for older people overall.

The coming economic headwinds are still likely to prove challenging across society. Many pensioners will face extreme difficulties if and when they cannot pay their bills. But young non-graduates felt more economically insecure before these economic shocks began to happen. Many of those people experience extreme circumstances – not being able to afford an emergency expense or having to borrow from friends and family for essentials in the preceding 12 months. As their circumstances change, so could their voting behaviour.

Just as we should not make blanket assumptions about economic security and voting intention, nor should we assume a simple link between economic security and cultural values. Specifically, economic insecurity and support for Brexit (or immigration concerns, or social conservatism) do not necessarily go hand in hand, in the Red Wall or beyond. Examining how these trends diverge by age and education helps us understand the current Conservative electoral base and how it could shift over time, depending on how external factors and its strategies change.

The graph below shows the likelihood of supporting Leave in the EU referendum by age (the dotted line), again using the BES internet panel in 2018, and the average level of feelings of economic insecurity (bold line) by age and education, focusing on non-graduates (and standardised scales to make a comparison). When reading this graph, remember that there are more older non-graduates in the electorate compared to older graduates, and more younger graduates than younger non-graduates (due to the expansion of higher education that has taken place over time).

Note: graph shows averages across the age distribution. Lines are smoothed local regression lines.

It suggests two clear reasons to support the Conservatives among older non-graduates; their position on Brexit and their sense of economic security. It follows that the Conservative Party should be concerned if these older individuals lose their economic security now, essentially removing one of two key drivers of support. There is no guarantee of holding onto Britain’s most economically secure voters through a culture wars frame, especially with the declining political relevance of Brexit.

Equally, the Conservative Party cannot ignore younger non-graduates. These more socially conservative voters (and some non-voters) are – at least given current Conservative policy directions – the likeliest future potential voters of the party. But there is also no guarantee of winning over Britain’s most economically insecure voters solely through a ‘culture wars’ frame. More economically insecure voters lean towards Labour and they are also more likely to be non-voters than other electoral groups.

Our research suggests this group could be a key electoral battleground in a number of key marginal constituencies. Using 2011 Census data, the following map shows a high distribution of younger non-graduates in hotly contested seats in England and Wales. People who tend to feel the greatest economic insecurity (younger non-graduates) live in constituencies that Labour has held onto (some seats in the Red Wall but also in many cities, and in south Wales), in seats that the Conservatives won in recent elections, and in key Conservative-Labour marginal seats that have flipped between the two largest parties. Ignoring these distributions could be electorally perilous. So would substantial losses of economic security among older Conservative voters.

Like everybody else, we do not know how the next election will pan out, and our study remains live. We will be adding new data and updating our findings as needed. But our findings so far suggest that each party’s ability to cater to the more economically insecure could be a key factor in their performance at the next general election. If the Tories want to win a record fifth term, they need to understand this.