Sarah Gall is a political data scientist and membership secretary for the UK’s Conservative Friends of Australia. She previously headed up political and policy research for the Prime Minister of Australia.

In Australia, one of the most talked about topics since the Labor Party came into office last year is the Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

The Voice is a proposed representative advisory body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and this year, Australians will vote in a referendum on whether or not to have this body enshrined in the Constitution.

Constitutional recognition for Indigenous Australians has long been fought for. Understanding this ongoing debate, however, ties in with the country’s torrid colonial past and the treatment of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who inhabited the land for more than 60,000 years prior to British settlement.

Australia’s colonial history, beginning in 1788, has featured undeniable atrocities waged against the Indigenous people, whose lands were taken from them. While these were recognised in 1837 by the British Parliament, the British settlers and Indigenous people did not, as in neighbouring New Zealand, enter into any ‘Treaty of Agreement’.

Instead, the British believed that a debt was owed and that all Aboriginal people needed protecting. Conditions and treatment varied, however, and there was a view that the Indigenous populations would become extinct.

As such, in 1901, when Australia became federated, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were explicitly excluded from the Constitution.

From the 1920s, Indigenous campaigners pushed for their equal rights and freedoms. These equal rights and freedoms were gradually achieved over the past 60 years, as Australians came to view the various policies once touted under the banner of protection as racist and discriminatory.

Achievements included the right to vote, the dismantling of state segregation policies, and the recognition of pre-colonial lands, which removed the idea (terra nullius) that Australia belonged to no-one prior to colonial settlement.

In 1999, John Howard proposed a preamble to be inserted into the Australian Constitution, recognising Indigenous people as the country’s first people. Specifically, the proposed preamble stated that the Australian people commit to:

“…honouring Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, the nation’s first people, for their deep kinship with their lands and for their ancient and continuing cultures which enrich the life of our country”.

As part of the proposal, a new section was also to be inserted into the Constitution to ensure that the preamble had no legal effect, did not give rise to any rights or obligations, nor could be used to interpret the Constitution or any Commonwealth laws.

The Howard Government pushed through the legislation for a Referendum on the Preamble in two days, without having spoken to Indigenous leaders.

During parliamentary debate on the Bill, the Labor Party disagreed with the term “kinship”, as they felt it did not properly reflect the relationship that the Indigenous people have with the land. Instead, they believed it should be amended to “custodianship”. This amendment was not agreed to and the Bill passed both houses unamended.

There was a very limited campaign for the preamble referendum question as it was a second question to what was seen as the more important question on whether Australia should become a republic. Both of these referendum questions were defeated, with the highest No vote being in electorates with high Indigenous populations.

Learning from these mistakes, and eager to push forward with reconciliation, Howard promised that if elected in 2007 he would hold a new, standalone, referendum question that proposed a new preamble and one which would be drafted in consultation with Indigenous leaders. As the Howard Government lost the election, this referendum did not come to fruition.

The Voice is now being proposed as an alternative way to achieve constitutional recognition for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Instead of symbolic recognition, the Voice aims to advise parliament on Indigenous policy issues, including health, education, and socioeconomic matters, and to help close the gap between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians.

In practice, it has been recommended that the Voice be made up of a 24-member panel with gender parity and include two members from every state, territory, and Torres Strait Islands, five from remote regions, and one representing mainland Torres Strait Islanders. This National Voice panel would be determined by 35 Local and Regional Voices.

Each Local and Regional Voice would decide how many members there would be and how they are determined, such as through election or through traditional laws and customs. Each Voice would also have their own secretariat team:

“…resourced by government at the regional level, which will facilitate and support all aspects of Local & Regional Voice work, including enabling and assisting community-level groups and arrangements as needed.”

The Voices, national and regional, would partake in “genuine shared decision-making” with all three levels of government. The Australian Parliament and Government would be “obliged” to consult with the National Voice on laws which overwhelmingly related to Indigenous people and be “expected” to consult on proposed policies and laws which have a significant impact on Indigenous people.

Where disputes occur, third-party mediation would be provided. If this failed, an independent review and recommendation would be given before a final decision was made. It is proposed that the final decision-maker would be “the relevant minister or ministers (Commonwealth with state/territory) alongside two respected, independent Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people”.

Both sides of the referendum argument agree that recognition of Indigenous people in the constitution as the first inhabitants of the land should occur. However, the Yes campaign see this being achieved by the Voice, while the No campaign believe amendment to the preamble would suffice.

What is unclear in this debate is why the Voice needs to be enshrined into the Constitution, as it could be created through legislation in Parliament.

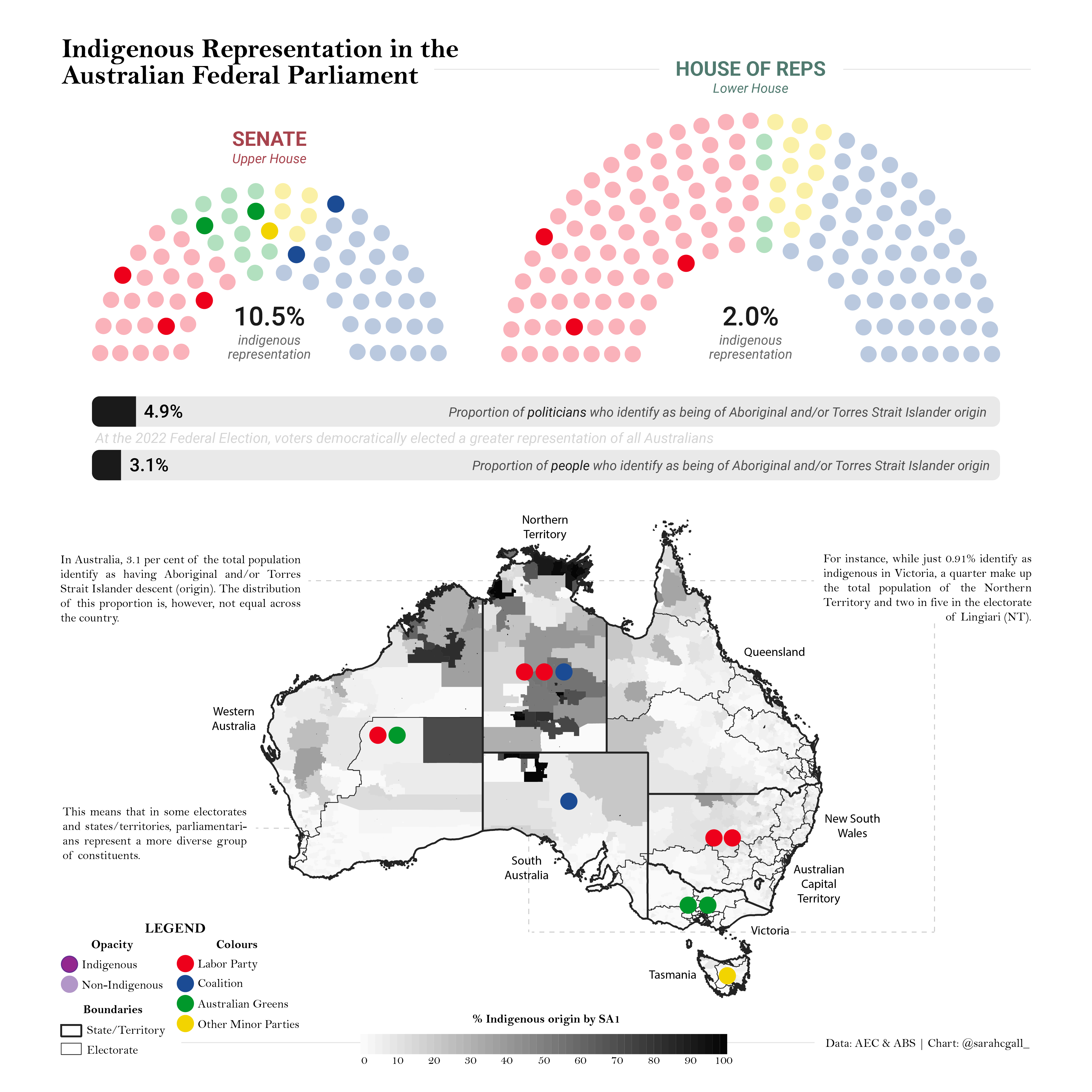

The Referendum Council argued that as Indigenous people only make up three per cent of the population, it is difficult for them to be elected to Parliament through a majority vote, and therefore “for their voice [to be] heard and for them to influence laws that are made about them”.

What this argument for better political representation disregards is that the populations of Indigenous Australians are not evenly distributed across the country. For instance, 0.91 per cent of the population of Victoria identify as Indigenous, compared with a quarter of those in the Northern Territory.

Despite this, the current indigenous representation of the Federal Parliament was nearly five per cent (10.5 per cent in the Senate and two per cent in the House of Representatives). These members of parliament do have a voice, and can influence laws just as those who are non-indigenous.

It is also unclear how the Voice will achieve the desired outcome of closing the gap, how much it will cost to set up and run, and how it is not yet another layer of bureaucracy.

Australia already sports many government departments and agencies, the over 30 land councils, the Prime Minister’s advisory council, the over 70 large Aboriginal organisations, and the 2700 Aboriginal corporations – not one of which would be replaced or repealed under the proposals.

The debate for this referendum has unfortunately begun to divide Australians, with many of those who support the Voice painting opposers as racist. This is despite many of those leading the No campaign being Indigenous themselves and advocating for “a better way”.

There is undoubtedly a lot of distrust of government amongst Indigenous people, understandable given previous generations actions. But Indigenous Australians do now have equal rights and freedoms, just as they also have equal representation and a voice in parliament.

What is difficult to see however, is how the Voice will reduce health or socioeconomic inequalities of Indigenous people and why it needs to be enshrined in the Constitution.