Lord Ashcroft KCMG PC is an international businessman, philanthropist, author and pollster. For more information on his work, visit www.lordashcroft.com.

Nicola Sturgeon and the SNP government have had an unusually tough few weeks. As my new poll of more than 2,000 voters in Scotland confirms, the damage is largely self-inflicted. In particular, most Scots – including many former SNP supporters – oppose Sturgeon’s position on gender recognition and the idea of framing the next election as a de facto referendum on independence.

Gender recognition

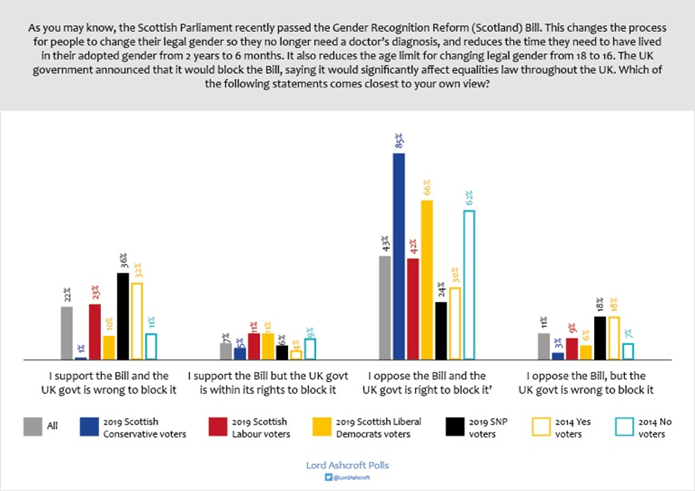

On the issue behind Sturgeon’s latest confrontation with Westminster – the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill – I found only just over one in five Scots (22 per cent) saying they supported the Bill and that London was wrong to block it. Nearly twice as many (43 per cent) said they opposed the Bill and the UK government was right to block it.

Overall, more than half (54 per cent) said they opposed the reforms, with 29 per cent in favour. Half said the UK government was right or within its rights to stop the legislation, with 33 per cent saying it was wrong to do so.

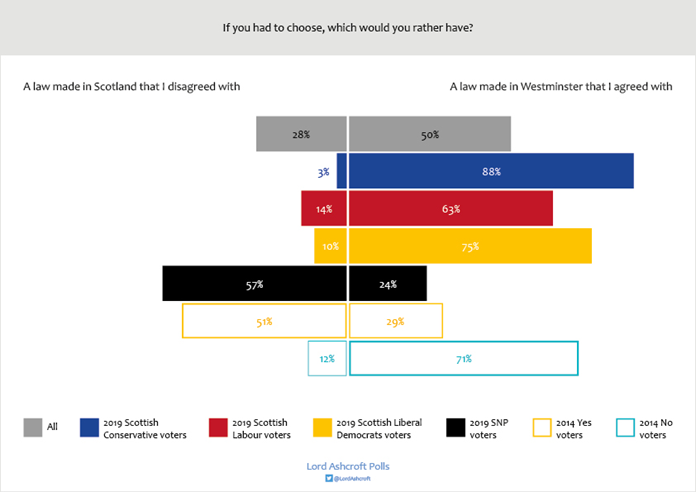

By 50 per cent to 28 per cent, Scottish voters said they would rather have a law made in Westminster that they agreed with than a law made in Scotland that they disagreed with. A quarter of those who voted SNP in 2019, and nearly 3 in 10 of those who voted Yes in the 2014 referendum, said they would prefer a London law that they agreed with.

Another repercussion from the gender recognition row has been the message it sends about the Scottish government’s agenda. When we asked voters what they thought were the most important issues facing Scotland, the top three answers were health and the NHS, the cost of living, and the economy and jobs.

But when we asked what three they thought Sturgeon and the SNP were currently treating as their main priorities, 65 per cent mentioned getting Scottish independence, followed by 46 per cent naming gender recognition and trans rights – with the NHS a distant third (22 per cent). Only three per cent of Scots said gender recognition was among the most important issues to them.

Scottish independence

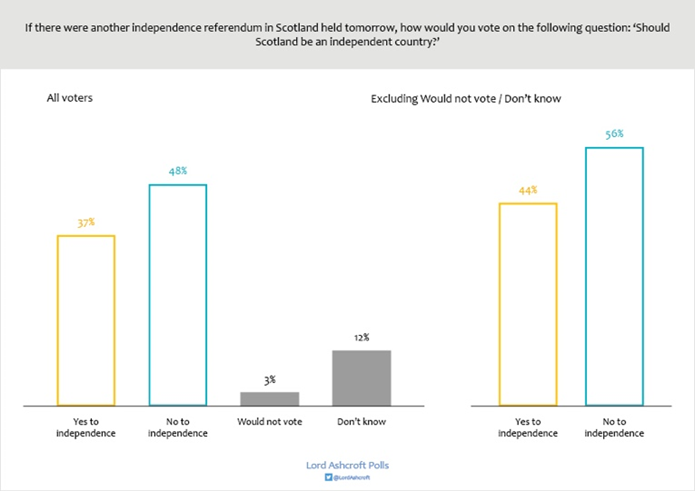

If a referendum were held tomorrow, 37 per cent said they would vote Yes to Scottish independence, with 48 per cent voting No and 15 per cent saying they didn’t know or would not vote. Excluding these voters, we find a 12-point lead for No, at 56 per cent to 44 per cent.

Scots were more likely to think such a referendum would reject independence (42 per cent) than produce a victory for Yes (33 per cent). Asked what they thought the result would be in five years’ time, they were more evenly divided: 36 per cent thought Scotland would vote Yes, 31 per cent thought it would vote No, and one third said they didn’t know.

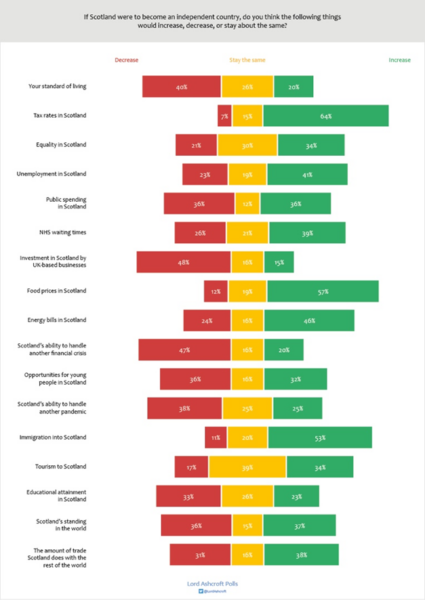

Scots as a whole tended to think tax rates, food prices, unemployment, immigration, energy bills and NHS waiting times would increase rather than decrease if Scotland became independent – as would equality, Scotland’s standing in the world, and the amount of trade Scotland did with the rest of the world.

They thought living standards, investment from UK businesses, Scotland’s ability to handle another financial crisis or pandemic, opportunities for young people and educational attainment would decrease rather than increase. They were evenly divided as to whether public spending in Scotland would rise or fall.

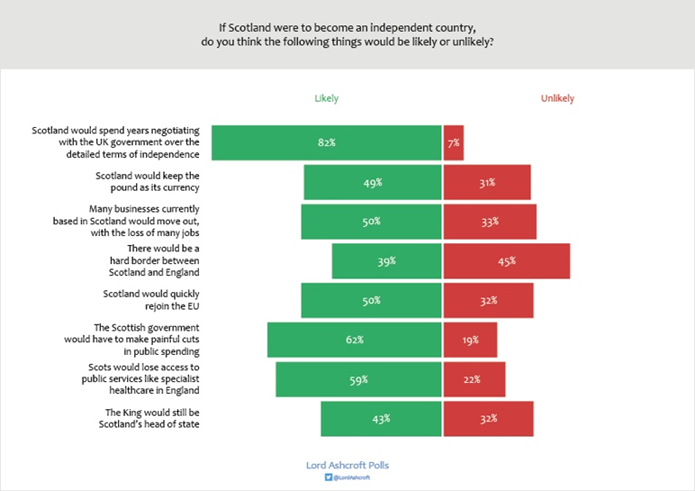

On balance, Scottish voters thought it more likely than not that an independent Scotland would keep the pound as its currency, that many businesses would leave, that Scotland would quickly re-join the EU, that Scots would lose access to public services like specialist healthcare in England, that the King would remain Scotland’s head of state – and (especially) that Scotland would spend years negotiating terms with the UK Government, and that the Scottish government would have to make painful cuts in public spending.

By a small margin they thought it more unlikely (45 per cent) than likely (39 per cent) than there would be a hard border between Scotland and England.

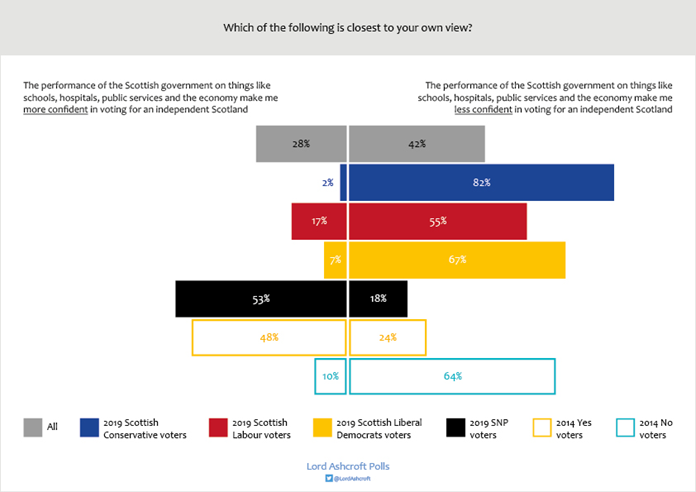

Only 28 per cent, including just over half (53 per cent) of 2019 SNP voters, said the performance of the Scottish government on public services and the economy made them more confident in voting for an independent Scotland. 42 per cent (including 18 per cent of 2019 SNP voters and 24 per cent of 2014 Yes voters) said the Scottish government’s performance made them less confident in voting Yes.

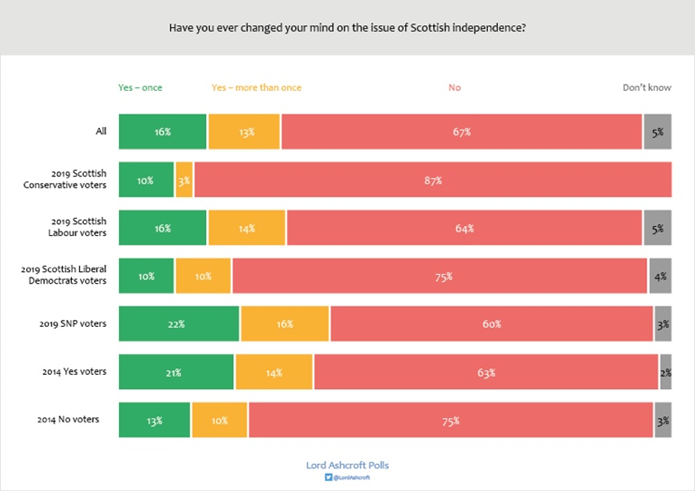

Nearly three in ten Scots (29 per cent) said they had changed their mind on the independence question at least once, including 13 per cent who had changed their mind more than once. Those who voted SNP in 2019 SNP (38 per cent), 2014 Yes voters (35 per cent) and those currently leaning towards the Greens (39 per cent) were the most likely to say they had changed their minds one or more times.

De facto referendum?

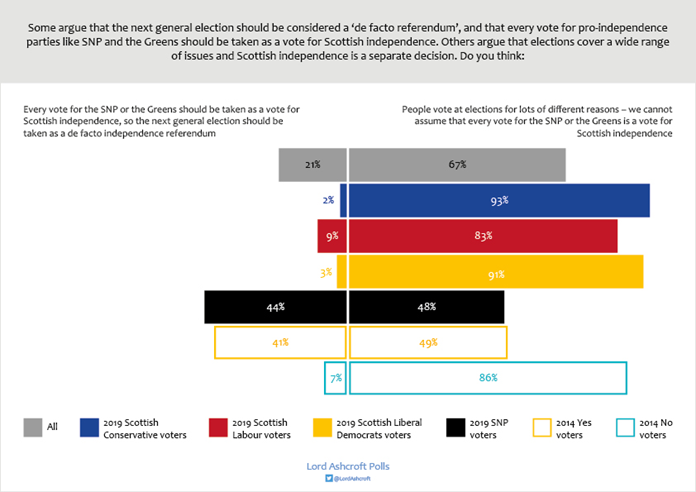

There was little support for the SNP’s plan to use the next general election to claim a mandate for independence. Only just over 1 in 5 Scots (21 per cent) Scots agreed that “every vote for the SNP or the Greens should be taken as a vote for Scottish independence, so the next general election should be taken as a de facto independence referendum”.

Two thirds (67 per cent) agreed that “people vote at elections for lots of different reasons – we cannot assume that every vote for the SNP or the Greens is a vote for Scottish independence”.

Current SNP supporters were the only group to support the de facto referendum concept (and only by 50 per cent to 41 per cent). Those currently intending to vote for the Green Party, whose leaders have signed up to the plan, opposed the idea by 56 per cent to 40 per cent – perhaps because, with only 64 per cent saying they would vote for independence tomorrow, they are not keen to have their election ballots read as a demand for constitutional change.

Among those saying they would vote Yes to independence tomorrow, 50 per cent said they thought the next general election should be treated as a de facto referendum; 39 per cent disagreed.

In any case, when we look at voters who put their likelihood of voting for a party at 51/100 or above, we find that the SNP and the Greens combined might struggle to command the majority of the electorate on which the plan depends: 40 per cent of likely voters were leaning towards the SNP, with five per cent leaning Green; Labour had 25 per cent, the Conservatives 18 per cent, the Lib Dems six per cent, Reform UK three per cent, and Alba two per cent.

EU membership

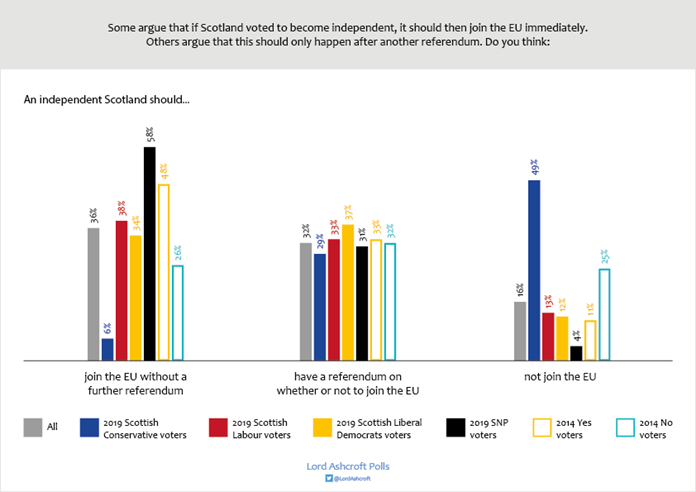

Scotland’s cabinet secretary for the constitution, has claimed that a Yes vote in a referendum would be a vote for an independent Scotland within the EU, so no further vote on EU membership would be necessary. I found that Scots voters do not see things the same way.

Only 36 per cent, including only just over half (58 per cent) of 2019 SNP voters and fewer than half (48 per cent) of 2014 Yes voters, think an independent Scotland should join the EU without a further referendum.

Just under one third (32 per cent) think an independent Scotland should hold a further referendum to decide whether or not to join, while 16 per cent – including nearly half (49 per cent) of 2019 Conservatives – think Scotland should stay outside the EU.

Politicians in a word

Finally, we asked voters what word or phrase came to mind when they thought about leading political figures. The combined answers speak for themselves…

Full data tables are available at LordAshcroftPolls.com.

Lord Ashcroft KCMG PC is an international businessman, philanthropist, author and pollster. For more information on his work, visit www.lordashcroft.com.

Nicola Sturgeon and the SNP government have had an unusually tough few weeks. As my new poll of more than 2,000 voters in Scotland confirms, the damage is largely self-inflicted. In particular, most Scots – including many former SNP supporters – oppose Sturgeon’s position on gender recognition and the idea of framing the next election as a de facto referendum on independence.

Gender recognition

On the issue behind Sturgeon’s latest confrontation with Westminster – the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill – I found only just over one in five Scots (22 per cent) saying they supported the Bill and that London was wrong to block it. Nearly twice as many (43 per cent) said they opposed the Bill and the UK government was right to block it.

Overall, more than half (54 per cent) said they opposed the reforms, with 29 per cent in favour. Half said the UK government was right or within its rights to stop the legislation, with 33 per cent saying it was wrong to do so.

By 50 per cent to 28 per cent, Scottish voters said they would rather have a law made in Westminster that they agreed with than a law made in Scotland that they disagreed with. A quarter of those who voted SNP in 2019, and nearly 3 in 10 of those who voted Yes in the 2014 referendum, said they would prefer a London law that they agreed with.

Another repercussion from the gender recognition row has been the message it sends about the Scottish government’s agenda. When we asked voters what they thought were the most important issues facing Scotland, the top three answers were health and the NHS, the cost of living, and the economy and jobs.

But when we asked what three they thought Sturgeon and the SNP were currently treating as their main priorities, 65 per cent mentioned getting Scottish independence, followed by 46 per cent naming gender recognition and trans rights – with the NHS a distant third (22 per cent). Only three per cent of Scots said gender recognition was among the most important issues to them.

Scottish independence

If a referendum were held tomorrow, 37 per cent said they would vote Yes to Scottish independence, with 48 per cent voting No and 15 per cent saying they didn’t know or would not vote. Excluding these voters, we find a 12-point lead for No, at 56 per cent to 44 per cent.

Scots were more likely to think such a referendum would reject independence (42 per cent) than produce a victory for Yes (33 per cent). Asked what they thought the result would be in five years’ time, they were more evenly divided: 36 per cent thought Scotland would vote Yes, 31 per cent thought it would vote No, and one third said they didn’t know.

Scots as a whole tended to think tax rates, food prices, unemployment, immigration, energy bills and NHS waiting times would increase rather than decrease if Scotland became independent – as would equality, Scotland’s standing in the world, and the amount of trade Scotland did with the rest of the world.

They thought living standards, investment from UK businesses, Scotland’s ability to handle another financial crisis or pandemic, opportunities for young people and educational attainment would decrease rather than increase. They were evenly divided as to whether public spending in Scotland would rise or fall.

On balance, Scottish voters thought it more likely than not that an independent Scotland would keep the pound as its currency, that many businesses would leave, that Scotland would quickly re-join the EU, that Scots would lose access to public services like specialist healthcare in England, that the King would remain Scotland’s head of state – and (especially) that Scotland would spend years negotiating terms with the UK Government, and that the Scottish government would have to make painful cuts in public spending.

By a small margin they thought it more unlikely (45 per cent) than likely (39 per cent) than there would be a hard border between Scotland and England.

Only 28 per cent, including just over half (53 per cent) of 2019 SNP voters, said the performance of the Scottish government on public services and the economy made them more confident in voting for an independent Scotland. 42 per cent (including 18 per cent of 2019 SNP voters and 24 per cent of 2014 Yes voters) said the Scottish government’s performance made them less confident in voting Yes.

Nearly three in ten Scots (29 per cent) said they had changed their mind on the independence question at least once, including 13 per cent who had changed their mind more than once. Those who voted SNP in 2019 SNP (38 per cent), 2014 Yes voters (35 per cent) and those currently leaning towards the Greens (39 per cent) were the most likely to say they had changed their minds one or more times.

De facto referendum?

There was little support for the SNP’s plan to use the next general election to claim a mandate for independence. Only just over 1 in 5 Scots (21 per cent) Scots agreed that “every vote for the SNP or the Greens should be taken as a vote for Scottish independence, so the next general election should be taken as a de facto independence referendum”.

Two thirds (67 per cent) agreed that “people vote at elections for lots of different reasons – we cannot assume that every vote for the SNP or the Greens is a vote for Scottish independence”.

Current SNP supporters were the only group to support the de facto referendum concept (and only by 50 per cent to 41 per cent). Those currently intending to vote for the Green Party, whose leaders have signed up to the plan, opposed the idea by 56 per cent to 40 per cent – perhaps because, with only 64 per cent saying they would vote for independence tomorrow, they are not keen to have their election ballots read as a demand for constitutional change.

Among those saying they would vote Yes to independence tomorrow, 50 per cent said they thought the next general election should be treated as a de facto referendum; 39 per cent disagreed.

In any case, when we look at voters who put their likelihood of voting for a party at 51/100 or above, we find that the SNP and the Greens combined might struggle to command the majority of the electorate on which the plan depends: 40 per cent of likely voters were leaning towards the SNP, with five per cent leaning Green; Labour had 25 per cent, the Conservatives 18 per cent, the Lib Dems six per cent, Reform UK three per cent, and Alba two per cent.

EU membership

Scotland’s cabinet secretary for the constitution, has claimed that a Yes vote in a referendum would be a vote for an independent Scotland within the EU, so no further vote on EU membership would be necessary. I found that Scots voters do not see things the same way.

Only 36 per cent, including only just over half (58 per cent) of 2019 SNP voters and fewer than half (48 per cent) of 2014 Yes voters, think an independent Scotland should join the EU without a further referendum.

Just under one third (32 per cent) think an independent Scotland should hold a further referendum to decide whether or not to join, while 16 per cent – including nearly half (49 per cent) of 2019 Conservatives – think Scotland should stay outside the EU.

Politicians in a word

Finally, we asked voters what word or phrase came to mind when they thought about leading political figures. The combined answers speak for themselves…

Full data tables are available at LordAshcroftPolls.com.